This is an expansion of a blog post I did in Thouin’s blog: What is Compersion?

When I first read Marie Thouin’s book What is Compersion? I was struck by the many ways she defines compersion:

- Compersion refers to a broad range of positive emotions experienced in relation to one’s intimate partner’s extra-dyadic intimate relations.

It is the joy, exhilaration, or excitement–or simply being happy–that your partner is happy with the loving, intimate experiences that they are having with their partner.

- Compersion refers to the broad range of positive attitudes, thoughts, and/or actions manifested in relation to one’s intimate partner’s extra-dyadic intimate relations.

What is contributory of this definition is that compersion is an ethic; take on the attitude of being compersic because not only do we feel happy when people are happy with others, but we should feel happy.

- Compersion refers to the broad range of positive emotions, attitudes, thoughts, and/or actions manifested in relation to another person’s gratifying experience in any context.

This third definition is independent of any context of non-monogamy, making “compersion” more expansive. Another way to describe the third definition is “sympathetic joy,” “Freudenfraude,” or simply feeling what is known as the common refrain, “I’m happy when you’re happy.”

However, there is an interesting approach that Thouin ends her book on. “Compersion is not only a feeling. It is also an orientation to relationships—a way people can choose to treat one another, based on principles of deep caring and collaboration.” This description has a democratic feel where compersion is now all-encompassing. This perspective goes beyond seeing compersion as just an emotional response or an ethical attitude in non-monogamous relationships and frames it as something more fundamental to how we relate to others.

The Expanding Horizon of Orientation

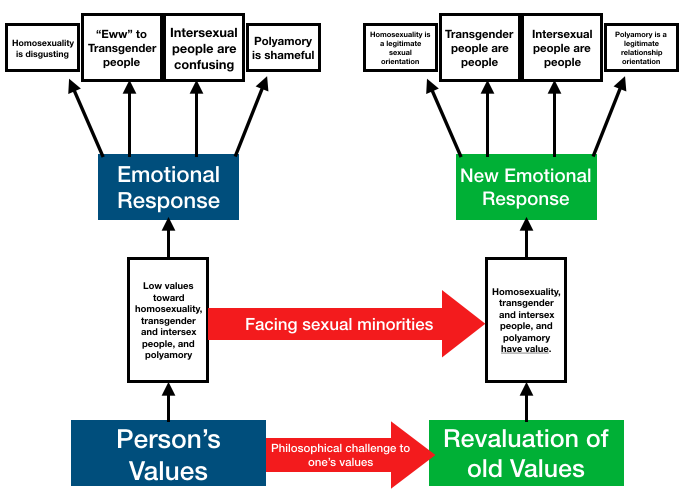

For a long time, orientation focused mainly on sexual attraction (like heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual, pansexual, asexual, etc.). Recently, romantic attraction has also been recognized as a type of orientation (such as heteroromantic, biromantic, homoromantic, panromantic, aromantic, etc.). This addition broadens our understanding of orientation. Now, individuals can distinguish between their sexual and romantic orientations. This clarity highlights the nuances of people’s experiences, emphasizing that having a sexual orientation doesn’t automatically imply a corresponding romantic orientation. So, we can say:

- Sexual orientation: Who you’re sexually attracted to

- Romantic orientation: Who you’re romantically attracted to

These frameworks have provided essential language for articulating our experiences, yet they remain focused on the self as the center of desire. We could consider many different forms of orientations. After all, there is a debate whether kink or being non-monogamous is an orientation. If they are, then kink as an orientation is what power dynamics you’re attracted to, or with non-monogamy, it would be what sort of relationship structure you are attracted to. Thus, different orientations could be:

- Whether kink might be an orientation toward certain power dynamics

- Whether non-monogamy might be an orientation toward relationship structures

I won’t go into the details about whether they are orientations or not, but let’s just say that if they are, then it expands our idea of orientation beyond what type of people we’re attracted to in a sexual or romantic way. Now we can say that we’re attracted to various activities with (sexualized) power dynamics, or what sort of sexual/intimate/romantic relationship structure we’re attracted to. How have others thought about orientation?

Three Different Views of Sexual Orientation

I’ll mention three philosophical perspectives that help establish the theoretical groundwork for compersion as an orientation. Robin Dembroff considers the common definition of sexual orientation problematic. When we feel sexual attraction, what is it that we’re attracted to? Is it their genitalia? Is it their gender presentation? Is it their secondary sexual characteristics? Our current definition is ambiguous. Another problem is that the definition is heteronormative. When we say “same” or “opposite,” it fits with gay people (“same-sex attraction”), heterosexuals (“opposite-sex attraction”), and bisexuals (“attracted to both”). But what about those who are genderqueer? Agender? Intersexuals? What’s the opposite of these identities? Our current definition leaves them out. And so, we need to expand our definition. Without getting into the philosophical weeds, Dembroff’s solution is to expand the concept of orientation beyond simply saying “gay” or “straight.” This critique opens space to expand our understanding of orientation beyond binary categories.

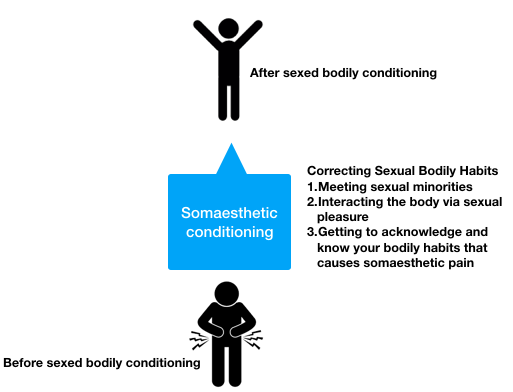

More directly relevant to my argument is Raja Halwani’s work, which connects orientation to well-being rather than merely attraction patterns. He challenges conventional understandings of sexual orientation by examining why certain sexual dispositions are elevated to the status of “orientations” while others remain mere “preferences.” At the heart of his argument is the observation that sexual orientation is typically regarded as a profound and essential aspect of personal identity. This special status demands explanation—why do we treat some sexual dispositions as fundamental to who we are while relegating others to the category of preferences? Halwani proposes that this distinction is best understood through the lens of sexual well-being. What makes a sexual disposition qualify as an orientation is tied to its relationship with a person’s overall well-being. Specifically, when the inability to act on a particular sexual disposition significantly diminishes one’s well-being, this serves as evidence that we’re dealing with an orientation rather than a preference. His central claim is that a necessary condition for a sexual disposition to constitute an orientation is that being unable to express or act on it meaningfully reduces one’s well-being. Moreover, Halwani recognizes that this reconceptualization implies that sexual orientation doesn’t have to be based on sex or gender; it could simply be based on the features that someone has. Here, I want to expand on Halwani’s theory and mark that it doesn’t necessarily have to focus on features that someone else has; rather, it could be how one finds different meaningful connections to others as an orientation. Halwani’s well-being criterion offers a powerful framework for Thouin’s notion of compersion as an orientation. If we observe that people who naturally experience sympathetic joy in others’ connections find their well-being significantly diminished when unable to express this relational stance, we have grounds to consider it an orientation rather than simply an attitude or ethical choice. The person oriented toward compersion doesn’t merely prefer to celebrate others’ joy; their ability to flourish depends on maintaining this open stance toward others’ connections.

Beyond the perspectives of Dembroff and Halwani, Sari van Anders’s Sexual Configurations Theory (SCT) offers a robust framework for understanding compersion as an orientation. Unlike traditional models that treat sexuality and sexual orientation as a single dimension focused on gender/sex attraction, SCT proposes a multidimensional approach that recognizes various independent parameters of sexuality and attraction. Van Anders’s SCT offers the gender/sex attraction as one dimension. Another dimension includes partner number preferences, which includes casual sex, monogamy, non-monogamy, and swinging. Relevant to our discussion is SCT’s distinction between eroticism and nurturance, which is another dimension Van Anders discusses. Eroticism refers to aspects of sexuality tied to bodily pleasure and arousal; nurturance encompasses warm, loving feelings of closeness. Just as SCT recognizes that one’s erotic and nurturant configurations may differ (e.g. someone might be heterosexual erotically but biromantic nurturance-wise, or someone could be monogamous but may allow non-monogamy if they’re in different time zones), compersion represents another distinct parameter in our relationship configuration. In particular, compersion operates within what Van Anders might categorize as the nurturance domain since others claim to feel warm, supportive feelings toward others’ connections. This positioning of compersion within SCT’s framework helps explain why some people seem naturally oriented toward sympathetic joy across various contexts, while others find such responses more challenging regardless of their other relationship preferences. Just as SCT recognizes that partner number preference (monogamy, non-monogamy) operates independently from gender/sex attraction, we can similarly position compersive orientation as an independent dimension that crosses these other configurations. Van Anders’ framework thus provides theoretical support for understanding compersion as more than an ethical stance or learned response—it becomes one dimension of how we are fundamentally configured in our capacity for and orientation toward human connection.

In the next post, I’ll go further in thinking of compersion as an orientation and consider some objections.